|

Paul

(Latham-Jackson) is often asked about the history behind

the F2; how and why it came to be designed and eventually

produced. This is his account of the story - currently

with few pictures, but more will be added shortly. It

was written in late 1990, but we have not altered his

words to reflect the passage of time. . . . . Paul

(Latham-Jackson) is often asked about the history behind

the F2; how and why it came to be designed and eventually

produced. This is his account of the story - currently

with few pictures, but more will be added shortly. It

was written in late 1990, but we have not altered his

words to reflect the passage of time. . . . .

"I

have been fortunate enough to have driven a wide variety

of some of the best sports cars produced since the war;

ranging from competition Ferraris down to the humblest

and tattiest of Spridgets and 'fifties Ford and Austin

specials. I've always had a soft spot for the products

of Lotus and Jaguar, but they have usually been too

expensive for me to own a really good example of either.

Like

many enthusiasts, I was disappointed when impending

American legislation threatened the future of the traditional

open-top two-seater. The development of the front-engined

sports car also came to a grinding halt when mid-engine

configuration became fashionable in the 'sixties. The

mid-engined road burners that followed always had a

crouching aggression that was most attractive, but for

reasons of space utilisation, gearbox type and position

and tyre fashion, they were less practical, generally

more expensive and rarely as elegant as the more traditional

roadsters and sports tourers.

The

driver appeal had changed too. On the race track - smooth

surfaced and built for flat-out competition driving

- the last iota of handling and roadholding must be

extracted from the complex system that is a race car

chassis. At much lower touring or even fast road driving

speeds, such cars are often unsuited to the unpredictable

road surfaces, narrow lanes and changeable weather that

so often seems to be part and parcel of the joyous experience

of driving a good car on the open road.

I

am a great believer in the old adage that racing improves

the breed, but I also believe that when racing cars

became primarily mid-engined and wide tyred they were

so far removed from road vehicles that it became difficult

to see how they were going to benefit the sporting road

driver. Of course there have been some desirable mid-engined

cars - who would deny the appeal of the Lamborghini

Muira or the Ferrari 308 GTB? - but they have tended

to be at the more expensive end of the market. When

Porsche (who have won an awful lot of sports car races!)

decided to produce a new generation of roadgoing sports

cars to replace their ageing 911 series, the 924 and

928 cars appeared with their engines at the front.

Of

course there have been other front-engined sports cars

produced since the 'sixties. Alfa Romeo soldier on still

with the Pininfarina bodied Spyder: a lovely body (designed

by the people responsible for the Daytona Ferrari) around

a competent chassis and desirable engine, but hardly

the car for Everyman! The Fiat 124 Spyder was a pleasant

sporting tourer but not for sale in the UK.

Here

in England we produced the TR7. I've always liked TRs

and looked forward to the announcement of the TR7, but

why, oh why, didn't they produce it with a soft-top

and Sprint engine in the first place? By the time these

options were available, the poor car had already established

itself (unfairly, I think) with a reputation as an emasculated

poseur's car. Part of the problem was undoubtedly the

American regulations, with their insistence on high,

indestructible bumpers and fears of acid rain, but the

main problem, I'm certain, was the body design. The

TR7 looked great from the front, but after that it turned

into a poorly executed pastiche of a mid-engined car.

Things

went a bit quiet after that, apart from Morgan filling

up their waiting lists and TVR producing the angular

Tasmin. Then Reliant turned out the SS100; with a body

designed (apparently!) by Michelotti, who should really

have known better, but with strong TR7 overtones and

lots of unnecessary detail moulding. They have since

learned their lesson and revised the body mouldings

to smooth out the shape and improve the car's appearance

immeasurably, though possibly too late to salvage dwindling

sales.

In

the meantime, the kit car industry had gathered a large

band of followers, mostly unhappy with what the mass

manufacturers were turning out. Not everyone wanted

to restrict their sporting motoring to a shopping car

with extra stripes or even a soft top, and few could

afford the silly prices beginning to be asked for the

older sporting machinery. By the late 'seventies any

five year old car was already beginning to rust very

badly. The kit car boom enabled the young man without

a fortune to put together an exciting open bolide using

the perfectly reliable mechanical bits from the decaying

family car. Lets face it; MG, Jaguar and Lotus all started

in a similar way. The problems with most of the early

'eighties kit cars was that they were so unrefined.

A doorless cramped machine with a massive ladder chassis

is fine for a few summer afternoons, but after a rainy

trip of a few hundred miles the appeal begins to wane.

At

this time I had left my work in motor racing and was

running the Specialist Cars workshop in Oxfordshire

in partnership with my wife, Julia. We spent some time

repairing and rebuilding the odd Lotus, Marcos or Ginetta,

but most of our business was building new kit cars for

people who had neither the time nor the facilities to

do it themselves. We built several of the better types,

such as Marlin and NG, and a few less delightful products

from manufacturers who shall remain nameless.

It

was during this time that the germ of the F2 idea began

to take shape. Because we were not aligned with any

one kit manufacturer, many potential customers would

ask our advice about which kits to consider, and it

soon became apparent that there was a significant demand

for something more sophisticated than the 'thirties

replicas that were so prevalent at the time. It couldn't

be a replica because most of the people involved knew

quite a lot about car history and didn't really want

to admit that they were driving a copy of something.

They wanted the real thing, and it had to be practical,

good looking, fast and relatively cheap to buy, so that

more money could be spent on things like leather seats

and decent wheels and tyres.

After

a lot of thought and nattering we came up with a basic

specification. The car would have to be an open two-seater

but with room behind the seats for the odd baggage or

baby. There would have to be adequate and simple weather

equipment and a boot sufficiently large and secure enough

for a couple of weeks' continental touring. In order

to propel this package along sufficiently rapidly we

would need something around 100 bhp minimum, and the

car would have to be low and smooth enough not to cost

a fortune in petrol.

We

prepared an exploratory prototype using an old TR4 chassis

and a heavily modified 1950's bodyshell and it was very

well received at Stoneleigh that year. We had obviously

got the formula right but we had to find a more suitable

donor car and re-design the slightly ungainly body so

that it was completely original, more practical and

a lot prettier. There was also the question of the chassis.

The TR frame was rather flexible without its steel bodyshell

so we had strengthened the GRP shell with foam-filled

sills and a massive rear bulkhead that incorporated

the aluminium fuel tank. There was also a strong tubular

steel hoop bolted through to the chassis and extending

across the car behind the dashboard. The body itself

formed a very rigid monocoque, and when it was bolted

to the TR chassis with the engine moved six inches back

the whole assembly was far more stiff than I'd expected.

I began to wonder if we could do without the chassis

entirely. We

prepared an exploratory prototype using an old TR4 chassis

and a heavily modified 1950's bodyshell and it was very

well received at Stoneleigh that year. We had obviously

got the formula right but we had to find a more suitable

donor car and re-design the slightly ungainly body so

that it was completely original, more practical and

a lot prettier. There was also the question of the chassis.

The TR frame was rather flexible without its steel bodyshell

so we had strengthened the GRP shell with foam-filled

sills and a massive rear bulkhead that incorporated

the aluminium fuel tank. There was also a strong tubular

steel hoop bolted through to the chassis and extending

across the car behind the dashboard. The body itself

formed a very rigid monocoque, and when it was bolted

to the TR chassis with the engine moved six inches back

the whole assembly was far more stiff than I'd expected.

I began to wonder if we could do without the chassis

entirely.

By

that time I had spent a couple of years driving a Davrian

as my personal car. The Davrian is a tiny streamlined

coupe with a Hillman Imp engine stuck in the back. They

were (and still are! ) immensely successful in Modsports

racing and just about the only things that could beat

them consistently were highly modified Lotus Elans.

The

Davrian also had a glass-fibre monocoque. Large section

sills were filled with hard-set polyurethane foam and

connected by thick GRP bulkheads and glass/plywood sandwich

floors. It worked perfectly. The only question was whether

the same principles could be applied to a rather larger

structure with a heavier engine. Careful study of composite

race car chassis and the foam-filled hulls of modern

racing yachts convinced me that it was not only possible,

but likely to be a far more practical method of construction

than the space frame.

Space

frames are wonderful for competition cars. They are

relatively simple to make (not easy to design though!),

very strong and simple to repair. Their main drawback

is that they do not keep the weather out. By their very

nature they define the areas of the car into engine

bay, passenger compartment etc, but then need panels

rivetted or glued into position to form bulkheads, floors

and footwells etc.

Our

experience at Specialist Cars had taught us that the

best way to make a cockpit weatherproof was to incorporate

the entire floor, sides and front and rear bulkheads

in one moulding which is almost impossible with a true

spaceframe. The monocoque lends itself very well to

this type of unitary construction approach!

Having

chosen - or rather, been presented with - the most suitable

construction technique, a suitable donor car had to

be chosen before we could carry on with the detail design

of the centre section. As the car was initially to be

produced in kit form, which means that the purchaser

has to find his own mechanical parts, we drew on our

Specialist Cars experience once again and decided that

it was essential to take all the component parts from

one donor vehicle. This would avoid asking people to

collect together a series of previously unrelated parts.

It

didn't take long to select the Triumph Dolomite, with

its well-located live rear axle, overdrive gearbox and

the wonderful 16-valve engine of the Sprint as an option.

With the exception of an oil pressure gauge it even

had a good set of instruments. I was initially worried

by the engine's reputation for overheating, but after

talking to a number of people who knew the engine well

I realised that it was something that could be overcome

with a little care and attention to detail. It is amazing

how a car can get a tainted reputation in the first

few months of its production life, and that taint will

stay with it long after the problem has been solved

- and even after the car has gone out of production.

The

only real problem with the Dolomite was the front suspension.

Firstly; the spring/damper units are mounted above the

top wishbone assembly, which means that they go far

too high for the low bonnet line I had envisaged for

the F2, and secondly; the steering rack is mounted behind

the front axle line rather than in front. This means

that if the engine were to be lowered in relation to

the front suspension it would also have to move a long

way back in the chassis. This in turn leads to complications

in the design of the exhaust system where it tries to

go through the passenger footwell. Both problems could

have been overcome by using front suspension units from

the Triumph Herald or Spitfire, but this would of course

have meant more cost to the customer. So we decided

to stick with the Dolomite parts and make them work. The

only real problem with the Dolomite was the front suspension.

Firstly; the spring/damper units are mounted above the

top wishbone assembly, which means that they go far

too high for the low bonnet line I had envisaged for

the F2, and secondly; the steering rack is mounted behind

the front axle line rather than in front. This means

that if the engine were to be lowered in relation to

the front suspension it would also have to move a long

way back in the chassis. This in turn leads to complications

in the design of the exhaust system where it tries to

go through the passenger footwell. Both problems could

have been overcome by using front suspension units from

the Triumph Herald or Spitfire, but this would of course

have meant more cost to the customer. So we decided

to stick with the Dolomite parts and make them work.

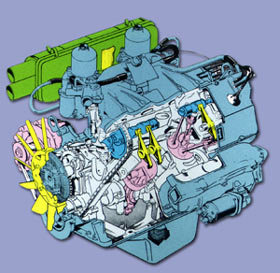

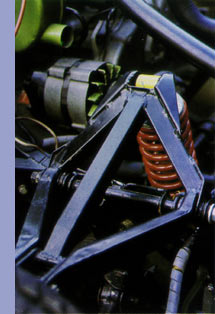

The

solution to the first problem is, I think, particularly

ingenious and has since become quite a feature of the

F2 design: The lower ball joint is not designed for

the sort of loading that would be imposed if we were

to mount the spring/damper unit on the lower wishbone,

even if there was anywhere suitable to mount it. Also,

since the engine had to be moved so far back to keep

the bonnet line down, there was now a large gap between

the radiator and the front of the engine. It seemed

an ideal place to put the springs and dampers; well

inboard and operated by rocker arms just like a modern

Formula One car! The rockers could be fabricated using

the original top wishbone pressings as a base and be

offered on exchange as part of the kit. The

solution to the first problem is, I think, particularly

ingenious and has since become quite a feature of the

F2 design: The lower ball joint is not designed for

the sort of loading that would be imposed if we were

to mount the spring/damper unit on the lower wishbone,

even if there was anywhere suitable to mount it. Also,

since the engine had to be moved so far back to keep

the bonnet line down, there was now a large gap between

the radiator and the front of the engine. It seemed

an ideal place to put the springs and dampers; well

inboard and operated by rocker arms just like a modern

Formula One car! The rockers could be fabricated using

the original top wishbone pressings as a base and be

offered on exchange as part of the kit.

Having

established this new relationship for the Dolomite parts

we then had an approximate outline around which to design

the body. Many people have asked me what influenced

the shape of the Latham and whether it is supposed to

look like some previous design. It isn't. Nor is it

intended to recreate the spirit of the fifties sports

racer or sixties road car. Most of the design decisions

on the bodywork were predetermined by our initial parameters,

the requirements of practicality, or the Construction

and Use Regulations which effect all cars to be driven

on public roads in this country. Certainly there have

been particular cars that I have admired, and most people

have been able to detect styling influences from one

period or another in the F2. But rather than borrowing

features from other cars I tended to study the way in

which their designers had overcome particular problems

and then apply these to my own design situation.

Headlights

were covered with plastic fairings rather than being

retractable in order to save cost and complication.

As many parts from the donor car as possible were used,

except where they were likely to compromise the sporting

character of the Latham, and that decision in itself

determined a great many of the design details; from

the type of lights we used to such things as door handles,

locks, instruments, pedals etc. So, as the various parts

were put into place the number of design decisions became

fewer, until I felt that I'd hardly designed the car

at all - I had just uncovered something that was already

there!

So,

there you are! The Latham F2 has now been designed and

built. Some people may not like the design - it isn't

perfect for me, so it's unlikely to be perfect for everyone

else, but a lot of thought and hours of development

went into arriving at the unique character and visual

appeal of the F2. Combined with this is its immense

performance potential and the practical detailing that

makes it as suitable for driving to the office every

day as for setting out on a tour of Europe for a few

weeks. Perhaps most important of all; when someone asks

you what you're driving you don't have to say "a

kit car", or "a GT40, but it's only a replica".

You can look them in the eye and say (proudly?) that

it's "a Latham - come and have a look!" So,

there you are! The Latham F2 has now been designed and

built. Some people may not like the design - it isn't

perfect for me, so it's unlikely to be perfect for everyone

else, but a lot of thought and hours of development

went into arriving at the unique character and visual

appeal of the F2. Combined with this is its immense

performance potential and the practical detailing that

makes it as suitable for driving to the office every

day as for setting out on a tour of Europe for a few

weeks. Perhaps most important of all; when someone asks

you what you're driving you don't have to say "a

kit car", or "a GT40, but it's only a replica".

You can look them in the eye and say (proudly?) that

it's "a Latham - come and have a look!"

Paul

Latham-Jackson

|