|

Two

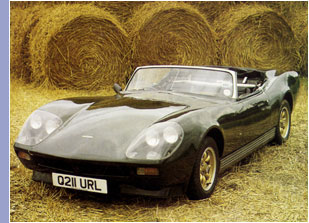

years after he wrote his first preview of the Latham

F2, Ian Hyne revisited Latham Sports Cars to have a

look at Paul Latham Jackson's original, and by this

stage, rather weary prototype. . . Two

years after he wrote his first preview of the Latham

F2, Ian Hyne revisited Latham Sports Cars to have a

look at Paul Latham Jackson's original, and by this

stage, rather weary prototype. . .

It's

been a long time coming but, overlooking the shortcomings

of a hardworked prototype development car, Ian Hyne

thinks the Latham F2 has a good deal to offer as a high

performance, touring car.

The name Paul Latham Jackson will be familiar to many

a long term kit car enthusiast as the name behind Specialist

Cars in Souldern, Oxfordshire who produced some superb

examples of good quality kits from 1981 onwards. I suppose

their most publicised efforts were a pair of NG TCs

that they built for export which, as well as being the

first V8 powered cars and overcoming all the problems

caused by differences between MG and Rover engines,

were also excellent examples of what could be achieved

with a little careful thought and imagination.

It is those same qualities that make the Latham F2 such

a hot prospect for future success even though the prototype

currently features many aspects which require improvement.

The idea for the car was hatched a long time ago while

the current car has emerged after four years dedicated

research and development. Indeed, it was Paul's experience

at Specialist Cars that prompted him to take his ideas

one step further. At that time, he built only the kits

which he considered to be worth the effort while his

contact with the industry showed him much that was very

primitive and of poor quality. He reasoned that there

was a demand for something more sophisticated than the

batch of period roadsters that seemed to head the field

in terms of quality and popularity so he set to work.

The

design parameters were many. The car had to be an open

two seater with room behind the seats for, as the blurb

so neatly puts it, 'the odd baggage or baby', it had

to be capable of accepting a hardtop for all year round

use, it had to have an easy to operate hood, it had

to have a decent sized boot sufficient to carry a couple

of weeks touring luggage, it had to have at least 100

bhp on tap and be smooth and light enough not to cost

a fortune in petrol. In addition, it had to be practical,

good looking, fast and relatively cheap and it had to

be fresh for the chap who didn't want to go round explaining

his car as a lesser copy of something else. (Click

image right to view enlargement) A tall order but

does the car live up to it? I think it does. The

design parameters were many. The car had to be an open

two seater with room behind the seats for, as the blurb

so neatly puts it, 'the odd baggage or baby', it had

to be capable of accepting a hardtop for all year round

use, it had to have an easy to operate hood, it had

to have a decent sized boot sufficient to carry a couple

of weeks touring luggage, it had to have at least 100

bhp on tap and be smooth and light enough not to cost

a fortune in petrol. In addition, it had to be practical,

good looking, fast and relatively cheap and it had to

be fresh for the chap who didn't want to go round explaining

his car as a lesser copy of something else. (Click

image right to view enlargement) A tall order but

does the car live up to it? I think it does.

As well as his experience of building kits, Paul has

also had the opportunity of driving a wide variety of

cars from competition Ferraris right down to the tattiest

Midget while he also spent a couple of years driving

a Davrian as his personal everyday transport. The car

was a glassfibre monocoque propelled by a Hillman Imp

engine and it was extremely successful in modsports

racing,' beating everything except heavily modified

Elans with far more power on tap. Having conducted experiments

with various chassis for his car, Paul then began to

wonder whether the same principles would ensure the

success of a larger car with a heavier engine, thus

the monocoque route was chosen.

The

central tub of the car is a complex moulding with the

sills and bulkhead moulded separately. When the sills

are added they are capped and filled with foam which

adds amazing strength for very little weight. The bulkhead

is double skinned for additional strength and the mechanics

are carried on two 16 gauge tubular subframes which

bolt to the tub through kevlar reinforced mountings

at either end. The

central tub of the car is a complex moulding with the

sills and bulkhead moulded separately. When the sills

are added they are capped and filled with foam which

adds amazing strength for very little weight. The bulkhead

is double skinned for additional strength and the mechanics

are carried on two 16 gauge tubular subframes which

bolt to the tub through kevlar reinforced mountings

at either end.

The choice of mechanics is also an interesting one when

everyone seems to automatically go for Cortina for the

convenience of the customer and their ready availability.

The Triumph Dolomite provides a far more sophisticated

package which includes a choice of two engines, a standard

1850 and the 16-valve Sprint version, an overdrive gearbox

which is the more usual to discover, a well located

live axle and even a good set of instruments. In addition,

Paul has designed his car to use as many parts as possible

from the donor even down to the door handles. The only

problem is the front suspension which mounted the coil

spring damper unit above the upper wishbone. However,

this one has been neatly overcome in a manner that adds

greatly to the road performance of the car (see

inset photo left, where the inboard dampers and rocker

arm can just be made out).

As stated, the front subframe bolts to the monocoque

and in order to balance the weight distribution, the

engine is moved well back in the frame. This leaves

a decent gap between the engine and the Dolomite radiator

which has been utilised for the front suspension. The

top wishbone has been modified to form a rocking arm

and the Spax adjustable coilover dampers are mounted

inboard.

Again,

everything else is standard Dolomite. At the back, the

rear suspension bolts straight into another 16 gauge,

tubular steel sub-frame and features the standard set

up, currently with standard springs and dampers. Behind

that, the boot floor is moulded to accept the Dolomite

fuel tank and spare wheel side by side and these are

protected by a tubular steel crumple zone. Again,

everything else is standard Dolomite. At the back, the

rear suspension bolts straight into another 16 gauge,

tubular steel sub-frame and features the standard set

up, currently with standard springs and dampers. Behind

that, the boot floor is moulded to accept the Dolomite

fuel tank and spare wheel side by side and these are

protected by a tubular steel crumple zone.

The car was designed to accept either 13' or 14' with

185/70 tyres while, for the purposes of experiment,

the car was fitted with 60 profile tyres on 13' rims

on the day of my visit.

The body design is also unique. To my mind it presents

a pleasingly flowing shape which will improve with the

fitment of the larger wheels and tyres, The bonnet is

a one piece, forward hinging unit which incorporates

the inner wheel arches. It is easily detatched from

the car by pulling two pip pins to afford unrestricted

access to the engine. The only slight criticism was

that the day I drove it was a little windy and it moves

about a great deal when raised so perhaps a little more

stiffness would not go amiss while the fixings when

closed, which comprise the Dolomite spring catch and

a Dzus fastener either side, still allow it to move

about. Of course, there is no danger but it is a little

disconcerting nevertheless.

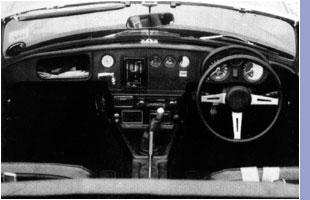

Moving back, the screen is MGB and the bonnet sweeps

up at the base to conceal the wipers. Behind the screen,

the dashboard, houses all the Dolomite clocks, heater

controls, ash tray, fresh air vents and stereo recess.

The main clocks are grouped in front of the driver along

with the Triumph multi warning light cluster and the

hazard warning switch. To the left, the three auxilliary

clocks are ranged above the manual switch for the Kenlowe

electric fan. Further over the heater controls are sandwiched

between the clock and a map light while below, the rest

of the bits and pieces are fitted into a specially designed

centre console.

The seats are excellent. They look very similar to Lotus

Elan but are the product of Latham Sports Cars while

the driving position is fine, if a little light on legroom

for the taller driver.

Behind

the passenger space, the boot sweeps up in a feature

now common on production cars as it allows the boot

space to be significantly increased and this car is

no exception giving a very good 11 cubic feet while

the boot, released from inside the car, also plays host

to the fuel filler.

The

doors are on the Dolomite hinges and though, these ones

sagged a little, it is a fault of worn hinges rather

than the design of the car. The windows, which wind

up on Spitfire mechanisms, are currently Perspex while

they will soon be replaced with toughened glass. The

shape suggests Lotus Elan again while there is no frame.

The leading edge features an aluminium channel but this

will be in stainless steel on production cars as a better

finish can be achieved and the end caps are easier to

fabricate. The

doors are on the Dolomite hinges and though, these ones

sagged a little, it is a fault of worn hinges rather

than the design of the car. The windows, which wind

up on Spitfire mechanisms, are currently Perspex while

they will soon be replaced with toughened glass. The

shape suggests Lotus Elan again while there is no frame.

The leading edge features an aluminium channel but this

will be in stainless steel on production cars as a better

finish can be achieved and the end caps are easier to

fabricate.

Overall, the package offers a stylish car with sophisticated

and powerful mechanics, spacious accommodation for two

and their luggage along with an advanced method of construction

that will endure and hold its value. I like it and,

when the completed production car makes its debut at

Stoneleigh in 1989, I'm sure many will agree.

Behind The Wheel

Opening

the door and dropping into the seat, you are aware of

how low the driving position is. For tall drivers, legroom

can be a little short but the pedals can be moved forward

by about six inches. The problem is caused by the long

travel clutch which has a very small master cylinder.

A larger cylinder will reduce the travel and allow the

pedals to move forward. The column is also adjustable.

Foot space for the passenger is also restricted by the

siting of the battery on the other side of the bulkhead.

All the clocks are easily visible through the attractive

Dolomite wheel and the rest of the controls are well

placed. The chassis frame provides mounting points for

either three or four point harnesses which is again

indicative of forethought and planning.

The

interior mirror gives a decent view over the high boot

line while the hood folds down below the level of the

boot so does not impede rear vision. The car was fitted

with an overtaking mirror but for me it was awkwardly

positioned and did not prove very practical. To my mind

it was the wrong tool for the job as far better mirrors

are available.

The

car was fitted with a standard 1850 engine mated to

an early four-speed box with no overdrive driving through

the lower 3.63:1 diff unit. At 680 kgs the car is a

good 5 or 6 cwt lighter than the donor so it was no

surprise when moving off that acceleration, even from

the tired development engine, was very rapid. Indeed,

Paul has taken performance figures on a disused airfield

where the car recorded 0 - 60 in 7.2 seconds and a top

speed of 122 mph! The red line is set at 6500 but in

its current state, it was not happy to go more than

5000 in the gears but that was plenty for rapid progress

round the lanes of Oxfordshire. The

car was fitted with a standard 1850 engine mated to

an early four-speed box with no overdrive driving through

the lower 3.63:1 diff unit. At 680 kgs the car is a

good 5 or 6 cwt lighter than the donor so it was no

surprise when moving off that acceleration, even from

the tired development engine, was very rapid. Indeed,

Paul has taken performance figures on a disused airfield

where the car recorded 0 - 60 in 7.2 seconds and a top

speed of 122 mph! The red line is set at 6500 but in

its current state, it was not happy to go more than

5000 in the gears but that was plenty for rapid progress

round the lanes of Oxfordshire.

On smooth roads, the car was a joy but come the bumps,

it seemed very harsh and rattly; unusual in a monocoque

design. However, ignoring the noise and the occasional

grounding of the skid plates. I pressed on.

It was a pleasure to drive a car fitted with a large

wheel as I always feel far more relaxed in control while,

on the handling side, the front end was superb pitching

into anything it was aimed at with well controlled enthusiasm

and minimal roll. The steering felt good and the column

transmitted marvellous feel. However, the rear end is

currently one inch lower than the production cars will

be and this, combined with the experimental fitting

of the 60-profile tyre, caused the bottoming. In addition,

the rear rode on standard springs and dampers which

we all agreed were too soft and, though I didn't push

it to break away, I felt it would not be difficult to

do, especially if fitted with the more powerful Sprint

engine.

The

other thing was that the engine tended to run out of

revs. I know it was tired but I reckon the overdrive

box with the 3.45:1 diff will be a much better bet driving

14 inch wheels with either 60 or 70 profile tyres. The

other thing was that the engine tended to run out of

revs. I know it was tired but I reckon the overdrive

box with the 3.45:1 diff will be a much better bet driving

14 inch wheels with either 60 or 70 profile tyres.

Apart

from the shortcomings of its current spec, I enjoyed

the car very much. The steering allowed you to place

it very accurately while the disc / drum brakes proved

very efficient at stopping the lighter charge. The box

was a delight with a good clean, fast change but it

was strange to find a box with such a wide gate. I kept

going from second to neutral as I failed to take the

stick far enough across.

On

the engine front, the standard 1850 gives 91 bhp at

5200 and 105 ft lbs torque at 3500 while the Sprint,

which is sure to prove the more attractive gives 127

blip at 5700 and 122 ft lbs torque at 4500.

So the car has certainly got performance with the availability

of a good deal more, it is attractive, spacious, good

to drive while it is also easy to live with.

The

hood frame is MGB while the hood is a special item which

uses the MGB fixings to attach to the screen and although

you have to stop and undo the poppers to lower it, when

attacked by a sudden burst of rain, you can reach over

your shoulder and pull it up in one go even at 30 mph.

When all the hatches are battened down, headroom is

fine even for the tallest chaps while the large rear

window maintains good rear vision. For parking or tight

manoeuvring, the high tail can be an obstacle but there

are plenty of cars that suffer in a similar manner while

the benefits of the design outweigh it.

Now,

what does it cost? Well the basic kit comes to you for

£1695 plus vat for a very comprehensive package

while, unfortunately, kit prices are set to rise by

about £200. However, don't be put off as I think

the price is still very reasonable for a car that offers

so much.

Finally,

as I said, the current demonstrator is a little tatty

having suffered in the course of a hard life as a development

and test car so, if you go and see it, don't be put

off by the ragged edges and less than pristine condition

while if you want to see a top example fitted with all

the right trim and other bells and whistles, go to Stoneleigh

next year. The car will still be around and, I think

it has a bright future. Finally,

as I said, the current demonstrator is a little tatty

having suffered in the course of a hard life as a development

and test car so, if you go and see it, don't be put

off by the ragged edges and less than pristine condition

while if you want to see a top example fitted with all

the right trim and other bells and whistles, go to Stoneleigh

next year. The car will still be around and, I think

it has a bright future.

The

company are currently in the process of relocating in

Oxfordshire but, for the moment, all enquiries can be

sent to . . .

With

thanks to Ian Hyne

Kit Car Magazine, November 1988, pages 54-56/63

Paul's

car remained the only F2 for some little while, even

after this article was written, and he continued to

delight in throwing the nimble beast around the back

lanes of Oxfordshire. Tired it may have been, but the

1850 engine continued for several more years, and the

car never did get the larger wheels, or stiffer springs,

that Ian Hyne wanted. Paul still has the car, and has

been talking about restoring it for some (not inconsiderable)

time.

To

visit the website of the current Kit Car magazine, click

this old version of the logo: To

visit the website of the current Kit Car magazine, click

this old version of the logo:

|